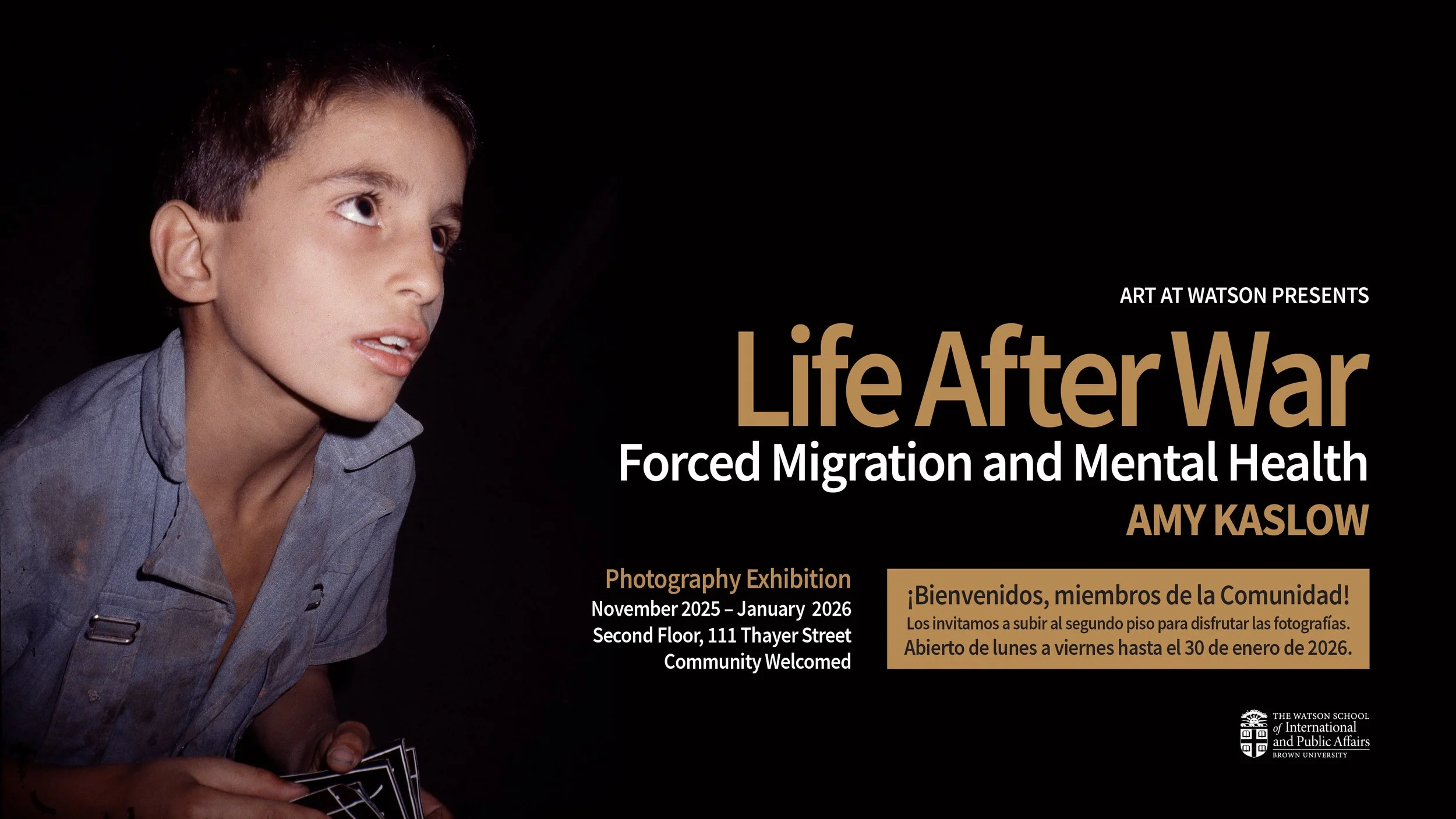

Art at Watson at The Watson School for International and Public Affairs at Brown University

LIFE AFTER WAR

FORCED MIGRATION AND MENTAL HEALTH

Nearly a billion people are forcibly on the move today: men, women, and children flung from their centers of gravity, from places their communities have known for generations. For now, these are survivors, remnants of conflict zones who somehow escaped the worst of humanity. Embarking on geographic journeys beyond the terror, most find that their trauma travels, too. And while they cut across many categories—including the ‘internally displaced’ who fled their homes but not their countries, the refugees and asylum seekers unable to return to their home countries, the impoverished economic migrants, the families hoping to reunite, and the untold numbers of stateless people—they share one very important trait. They are desperate.

The United Nations High Commission of Refugees (UNHCR) tracks migrants entering mostly low- and middle- income nations, which sorely lack resources and/or resolve to meet non-citizen needs. Fleeing to fledgling or established democracies often makes their emotional turmoil worse with unwelcome responses from unwilling hosts, including the United States and European countries responsible for many of the regional conflicts that exploded the populations in the first place. The World Health Organization (WHO) documents how displacement aggravates and ignites mental illness among forced migrants, and in 2023 it found a staggering twenty percent of the entire global population suffering. Since WHO first sounded this warning, Russia has ravaged Ukraine, Israel has leveled Gaza, and across every continent, many dozens of other nations are wracked by civil war. Piling onto this of course is Mother Nature’s wrath, the devastating fires and savage storms that push out entire populations.

‘Traumatized’ has become a major demographic. Victims live with their perpetrators and among the silent eyewitnesses to unspeakable atrocities. They are crammed together behind high fences of refugee camps, stuffed into detention centers, restricted to the most blighted, overcrowded parts of town and thrust into rural, remote oblivion. Theirs is a dual existence of density and isolation. They have close, if not cramped physical contact, yet their communication is blocked by anxiety, depression, extreme agitation, and psychosis. Most cultural norms react with fear or punishment, leaving individuals and families to hide troubles at home, in transit, and in their new host country.

The mismatch between survivors’ mental health needs and their hosts’ refusal to help portends immediate challenges to our very agency as individuals and to our global longterm stability. The number of people damaged and disturbed promises to increase, given the nonstop growth in regional conflicts. Our failure to reverse this trend will leave us a world in which most of us are emotionally unstable. And as peoples, we will become even more vulnerable to manipulative leaders who favor control over freedom, autocracy over democracy. For a clear look at today’s surge of govern and grab autocracies and the severe impact on mental health, the Kennedy School, the National Institutes of Health, and Freedom House all have pointed studies examining the brutal consequences for those who cannot push back, and the pall over the rest of society.

Life After War transports us to more than a dozen countries, some decades into their post-war years, others still in daily conflict. Historical context, here and now conditions, and future concerns for growing populations are all real and representative of places where development demands are vast, human engagement is critical, and investment can go far. Individually and collectively, all of us define the capacity to engage – we are the world’s students, its civic minded, its religiously affiliated, its politically motivated, its entrepreneurs, its investors, its young professionals, its wise and skilled retirees. We are all equipped to help create change.

Amy Kaslow Washington, D.C. September, 2025

This exhibition will be on view at The Watson School for International and Public Affairs at Brown University through January 15, 2026.